A unique 1897 book by Hugue Imbert comparing the light in Rembrandt's art to tonalities in Wagner's music was discovered by Maria Danova, independent scholar, in the library of the Russian Institute of Art History, St. Petersburg, founded in 1912 by Count Zubov, where it landed in 1994. In addition to recovering the translation by B. L. O'Donnell, Maria has provided useful links whenever possible, and compiled both visual and audio illustrations to enhance the experience. We hope that this delightful comparison between visual and musical arts will bring AWE to all of our readers.

Fragment of the cover of Imbert’s essay in French

The first page of Imbert’s essay in French

By Hugue Imbert,

Translated from the French by B. L. O'Donnell, from the edition:

Studies in Music by Various Authors, reprinted from "The Musician", edited by Robin Grey. London, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co., Ltd., 1901, pages 152-167.

Arranged by Maria Danova

LIGHT AND SHADE IN ART

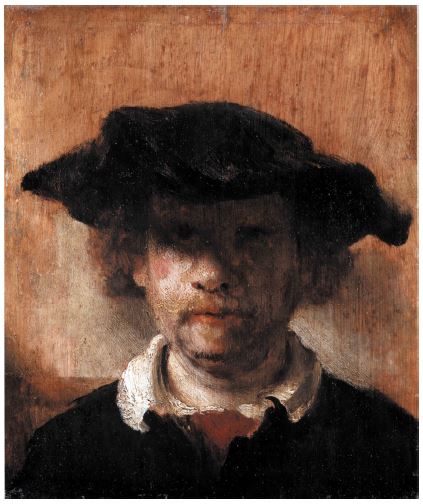

Rembrandt, Self-portrait, oil on canvas, 1660, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

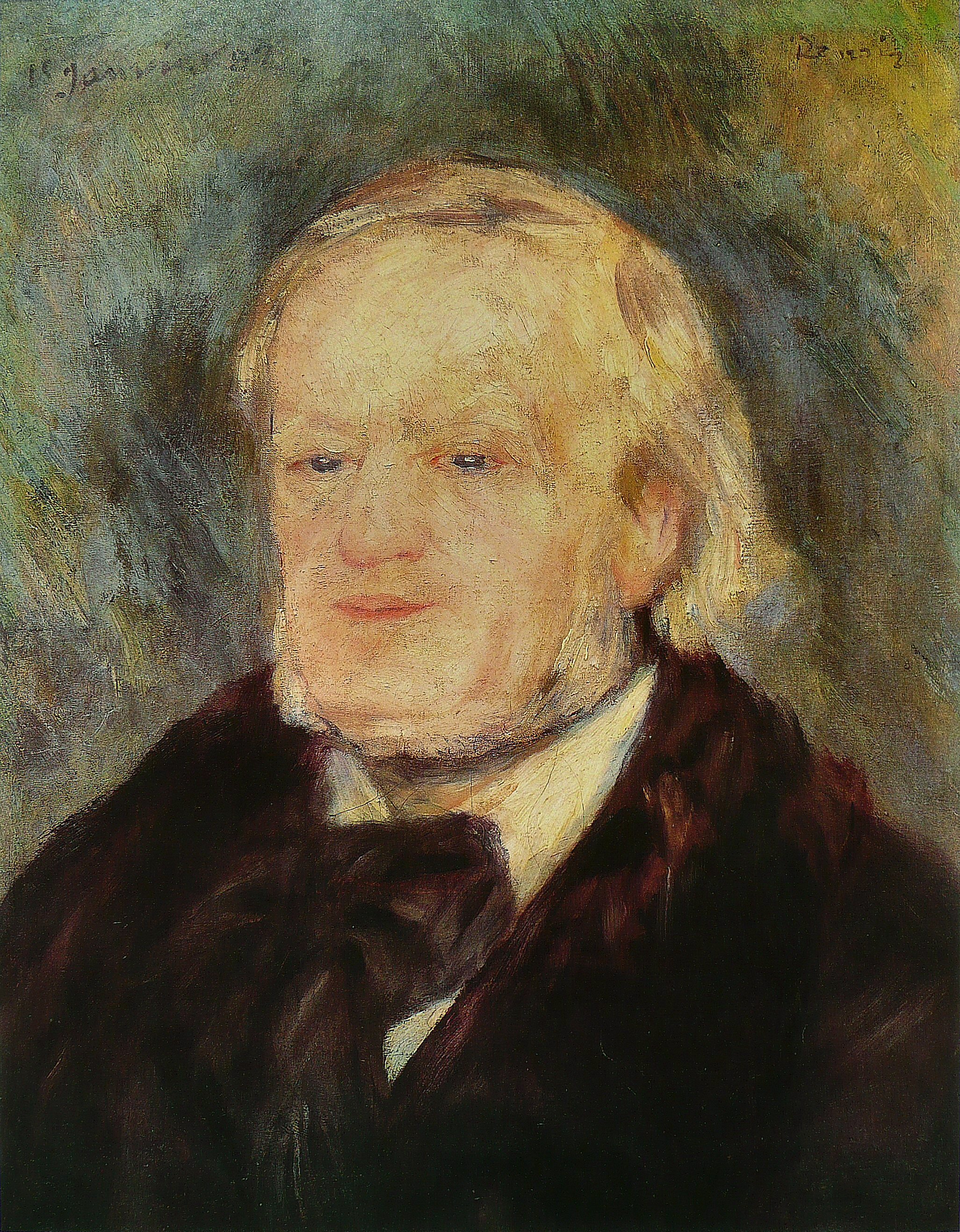

Portrait of Richard Wagner, oil on canvas, 1883, by Giuseppe Tivoli, Civico Museo Bibliografico Musicale, Bologna, Italy

LIGHT and shade, harmony and dissonance! Do not these four terms, which determine the limitations of the visual and auditory faculties, also include painting and music, the visible and the invisible world, the world of forms and that of substance? What an infinite number of luminous vibrations exist between a midday sky and a starlit night, through all the shades of daybreak and of dawn, of sunset and of twilight! Can we not trace a multitude of sonorous vibrations in the murmurs of a crackling forest in which are predominant the majesty of perfect harmony and the shrill hissing of a storm at sea, when all the superposed notes tear and annihilate each other in a furious and weird affray? Painting, which reflects the visible world by the aid of colour, and music, which expresses the invisible world of sentiments, exist between the two extremes of light and shade, harmony and dissonance, both corresponding to those two conditions of the soul known as joy and sadness.

Rembrandt, David Playing the Harp before Saul, oil on canvas, date unknown, Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Our senses do not enable us to detect anything in common between painting and music, which appear as irreducible to one another as light would be to sound. But our souls tell us that they correspond to each other, just as the external world communes with the internal world, by means of thoughts and sentiments. It is worthy of notice that music, whether symphonic or vocal, evokes images at its highest pitch of intensity, just as perfect painting can engender a rhythmical and melodious vibration of the soul, similar to musical waves. A temperament, ever so commonplace, could not listen to a symphony of Beethoven, to a fragment of Berlioz or Wagner, without perceiving a vision of landscapes or human dramas. No one, however devoid of sensitive feeling, could gaze upon one of Correggio's nymphs, or upon a Madonna of Memling, or a prophet of Michelangelo, without feeling certain vibrations of the innermost self, mysteriously impelled by human or heavenly harmonies. There is thus a 'chiaroscuro' and colours in music just as there are harmonies and tones in painting. The two arts meet at that depth of the soul where sentiment and form are born of a common idea, where the vibration of sentiment creates visible form, and where the beauty of the form awakens the musical vibration.

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait in Motion, oil on panel, 1634, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Gemäldegalerie

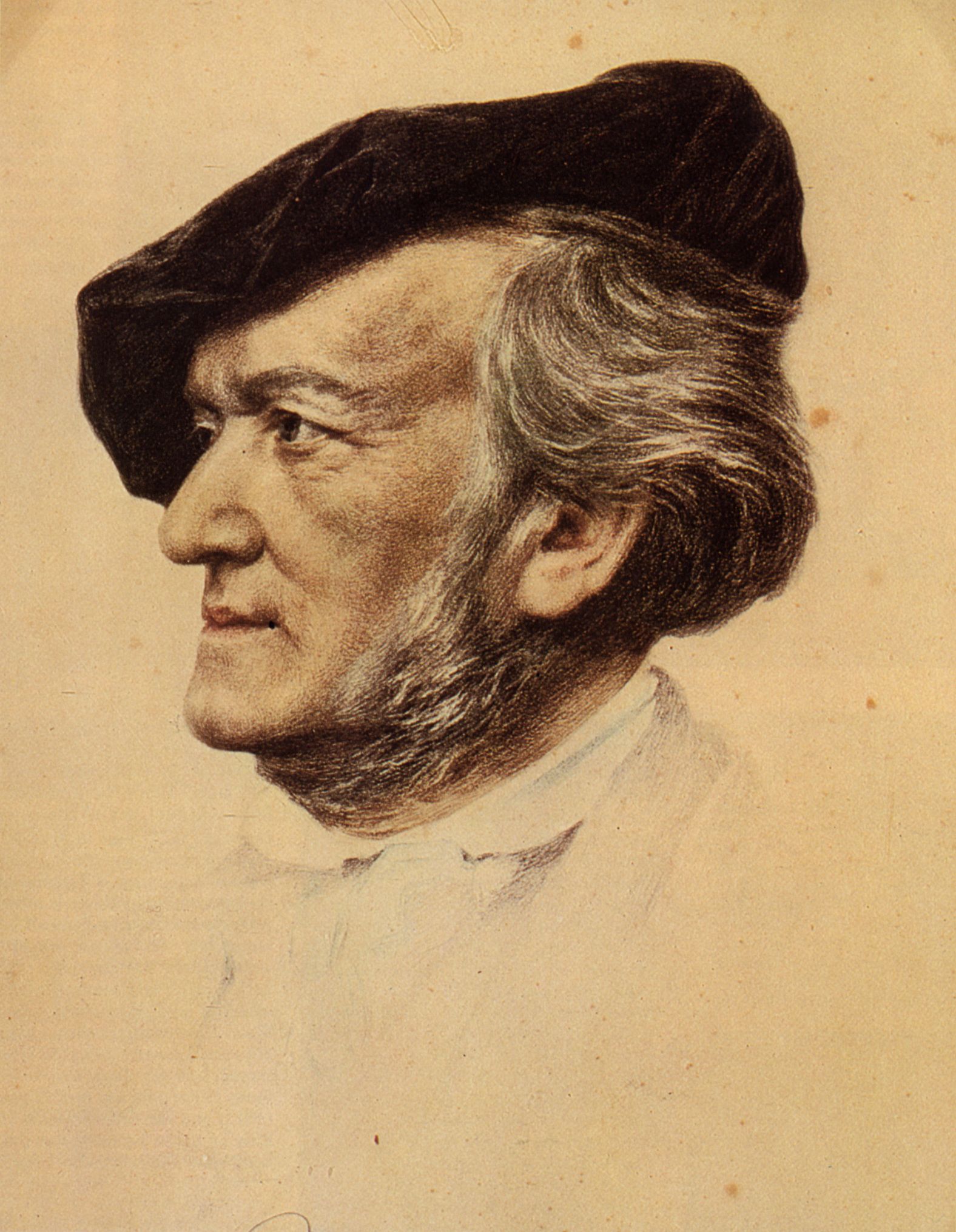

Portrait of Richard Wagner by Franz Seraph von Lenbach, oil on canvas, ca. 1870, Alte Nationalgalerie, Berlin

The originality of painter and musician are shown in the way in which they oppose light to shade, harmony to dissonance. In this, Rembrandt and Wagner can be considered brothers, not because they are identical in every detail, but because their temperaments are so much alike. They show the same contempt for hackneyed methods, the same yearnings for new ones, the same delight in rare and intense sensations. But the strongest link between them is that wonderful gift they both possess of awakening in us the sense of external life, of stirring the inner man by effects that are both delicate and violent, of bringing, as it were, the soul into light, by a clash between light and shade.

In this rapid study of the two great masters, we purpose submitting some examples of the secret but striking correlations between their sensitiveness and their systems. We shall then endeavor to show the differences that exist between them.

...

It has often been said that a great genius is not produced all of a piece, that he is the result, the echo of all the efforts and the aspirations of many preceding generations. Rembrandt undoubtedly can be traced from Lastman and Pynas, while Wagner owes his origin to Gluck and Weber. But have they not vastly extended the modes of their masters and predecessors? They have engraved upon steel the timid lines of the past and interpreted in a strong and majestic language the first stammerings of the muse.

Do they not seem to have broken off with past traditions, to have snapped the chain of art? Have they not introduced into this art, apart from new plastic beauty, sublime moral beauty, the poetry of the supernatural and that intense passion? They are the inventors of a sublime aestheticism, the creators of an ascensional movement.

How has this understanding come about between two men so separated by time and distance? This is a mystery that can only be explained by the instinct which they both possessed of a new poetry. They have made their art immaterial: in their creations we find nothing but the human soul. They both revered Psyche; and for them she unfolded her wings.

...

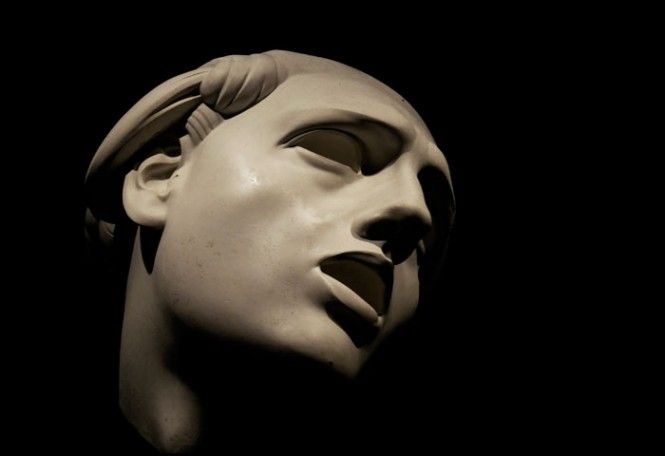

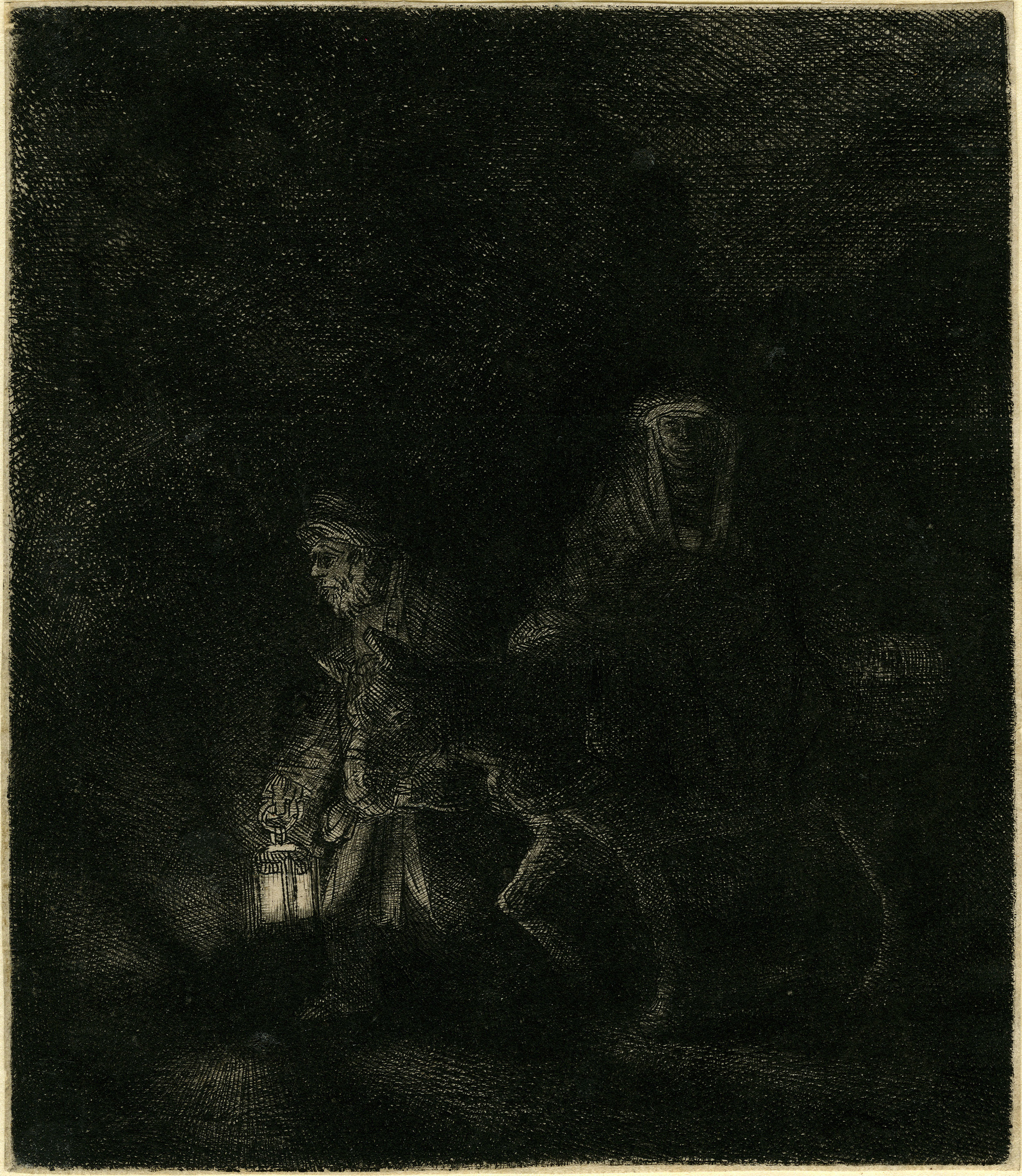

Admire Rembrandt's masterpieces in the principal museums of Europe, read the beautiful books that have been written about this great genius, in which his pictures, his drawings, and his sketches are faithfully reproduced (note: the most important of these works is entitled Rembrandt, His Life and Works, and His Times, by Mr. Emile Michel, Membre de L’Institut). The originals and the reproductions, especially those consecrated by Van Rijn to the translation of Divine subjects, to the principal stories of the Bible and the New Testament, seem to create the same weird impression as do those musical pages with which Wagner resuscitated the olden legends. In both their works mystery hovers, the pathos and the magic of the 'chiaroscuro,' of light and shade, are felt.

When Rembrandt attacks scenes that have often been painted by his predecessors or by his contemporaries, when he is dealing with the various episodes of the life of Christ, the Crucifixion, the descent from the Cross, the Entombment, the Ascension, what sublime lights he imparts to his visions that go back to the early periods of Christianity! He certainly ignores tradition, conventional laws; but all the scenes depicted by him have the hallmark of genius, of genius made of light and shade, of that genius that bears you away to dreamland.

Rembrandt, Raising of Lazarus, etching, 1642, Morgan Museum and Library, New York

AWE Tip: Morgan Library & Museum digitized collection of Rembrandt etchings: about 500 works

In that wonderful etching in which he makes Jesus say to Lazarus, 'Rise and walk,' he masses the shades behind Christ and projects the stronger light upon Lazarus rising from his coffin and upon the bystanders, who shrink back in fear and amazement, and the whole constitutes a formidable crescendo in the intense light that illumines the drama. Mary alone comes forward, arms outstretched, for she has recognized Lazarus. This is indeed the miraculous scene, the extraordinary deed of a resurrection surrounded by all the majesty of emotion which it deserves.

Christ has only to raise His left hand, and a sudden light is produced, giving a supernatural character to the episode. Clad in a long toga, standing barefooted upon the flagstones, He towers over the whole scene by His greatness and His powerful will.

Rembrandt, Raising of Lazarus, oil on panel, c. 1632, LA County Museum of Art

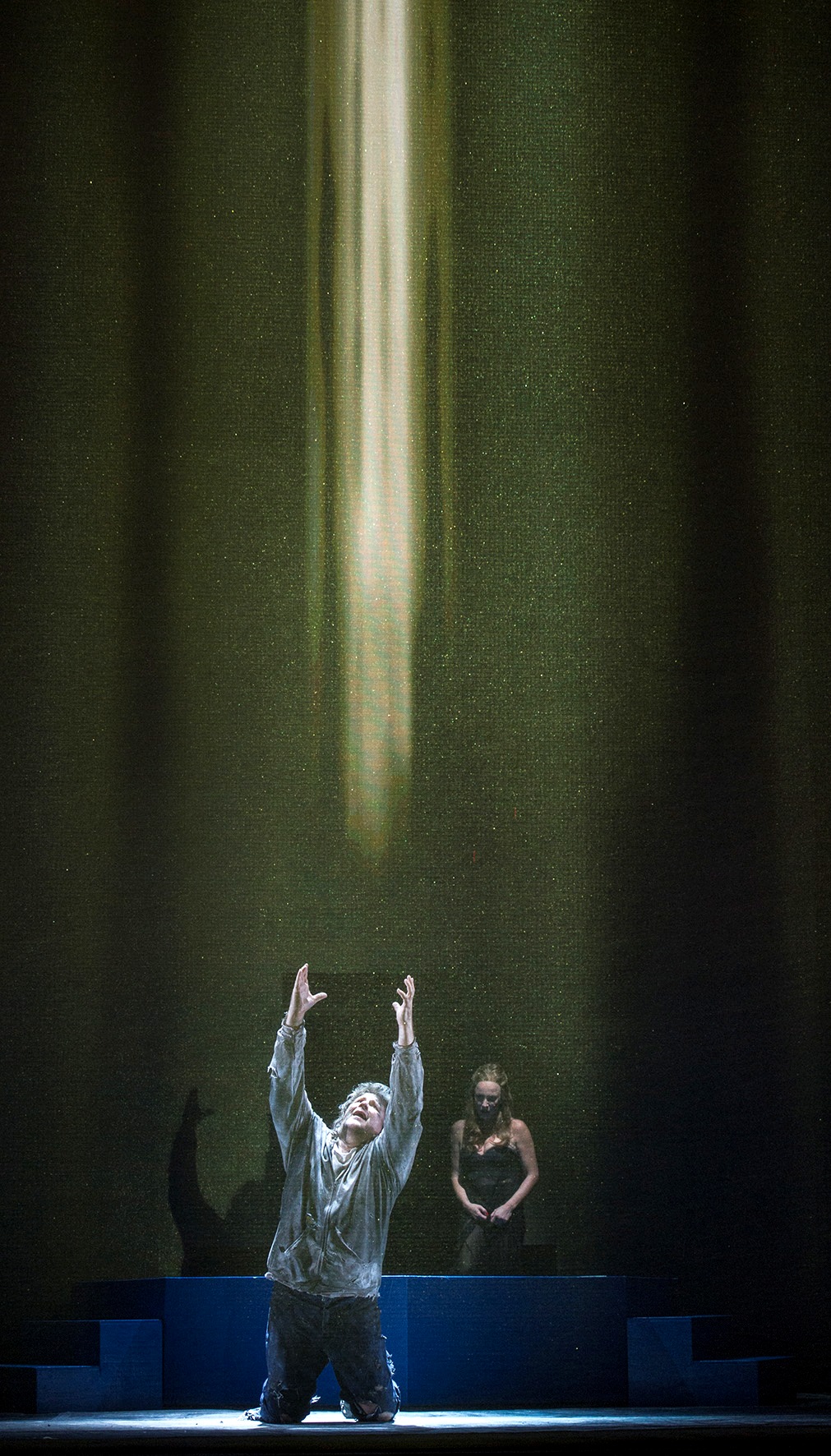

Do we not find identical effects of light and shade, so dear to Rembrandt, produced in the Temple scene of Parsifal, that majestic and seraphic page of the drama that was so justly christened The Canticle of Canticles of Divine love? While the orchestra plays the characteristic march, to which are soon added the sounds of the horns and the chimes of the bells, the whole panorama of the different places that Parsifal and Gurnemanz have passed through on their way to the holy mount of Monsalvat is unfolded in one progressing scene. Then we see the interior of the Temple with its huge cupola, whence fall the sounds of the bells,

and whence soon will descend an intense, an almost supernatural light.

Temple of the Holy Grail, stage set by Paul von Joukowsky for the first Parsifal production at Bayreuth, 1882, Met Opera Archives

From the depths of the sacred building, the slow procession of the knights of the Holy Grail proceeds, singing the chorus on the same motive as that of the orchestral march. Gradually light is thrown on the stage. The knights gather round the Communion tables, followed by their equerries and the lay brothers, the former carrying King Amfortas, still suffering from his wound, the latter bearing the tabernacle which contains the Grail. The emotion increases, as the voices of the knights in the midst of all this pomp are heard in gradations, together with those of the youths in the center, and of the children at the top of the cupola. It is indeed the unfolding of a mystery with alternatives of dazzling light and dark tenebrae, just as noticeable in the scenery as in the music. Then comes the terrible episode in which Amfortas describes his sufferings, refuses to celebrate the Divine mystery, and finally consents to do so, remembering the promise of redemption. This pathetic scene, the anguish and sorrow of which baffle description, puts an effectual stop to the prayers of the knights, the invocations of the boys, and the ineffable canticle of the children, ‘Uncover the Grail.' And then the act of consecration begins, in the darkness of the twilight that invades the temple, the supper theme being delineated by the orchestra and the children's voices, who sing while Amfortas prays:

Take this bread, it is my body,

Take this wine, it is my blood,

Which my love has given thee.

AWE Tip: To follow the text of this and the following fragments in parallel German and English, search for the initial phrase in the respective libretto: http://www.rwagner.net/e-t-opere.html

Can we not liken the long tremolo of the basses to an effect of darkness, of shade, which throws out in bold relief the theme of Redemption?

As Amfortas slowly raises the Grail cup and the scales above the kneeling knights, the darkness is replaced by a dazzling light which falls upon the sacred cup, and is refracted by it into a thousand brilliant coruscating rays.

A still from the documentary Parsifal: The Search for the Grail. Directed by Tony Palmer. Conducted by Valery Gergiev. Great Performance Series, 1999

AWE Tip: Wagner’s Parsifal in Notes and Pictures

The supper-theme is interpreted again by the orchestra, with all its wealth of sound. Little by little these musical splendors die away; the knights rise, the feast begins, with the songs of the knights alternating with those of the children and youths; the knights then solemnly leave the Temple after the feast, while the tabernacle of the Grail is being removed. Once more the orchestra, having unfolded the theme of faith, takes up the motive of the first march.

Here occurs that short and very curious episode, during which Gurnemanz remains alone with Parsifal, upbraids him for his stupid silence, and throws the artless one out of the Temple. But, in the cupola, a heavenly voice is heard, supported by the chorus of youths and children, singing Blessed are those who have Faith.

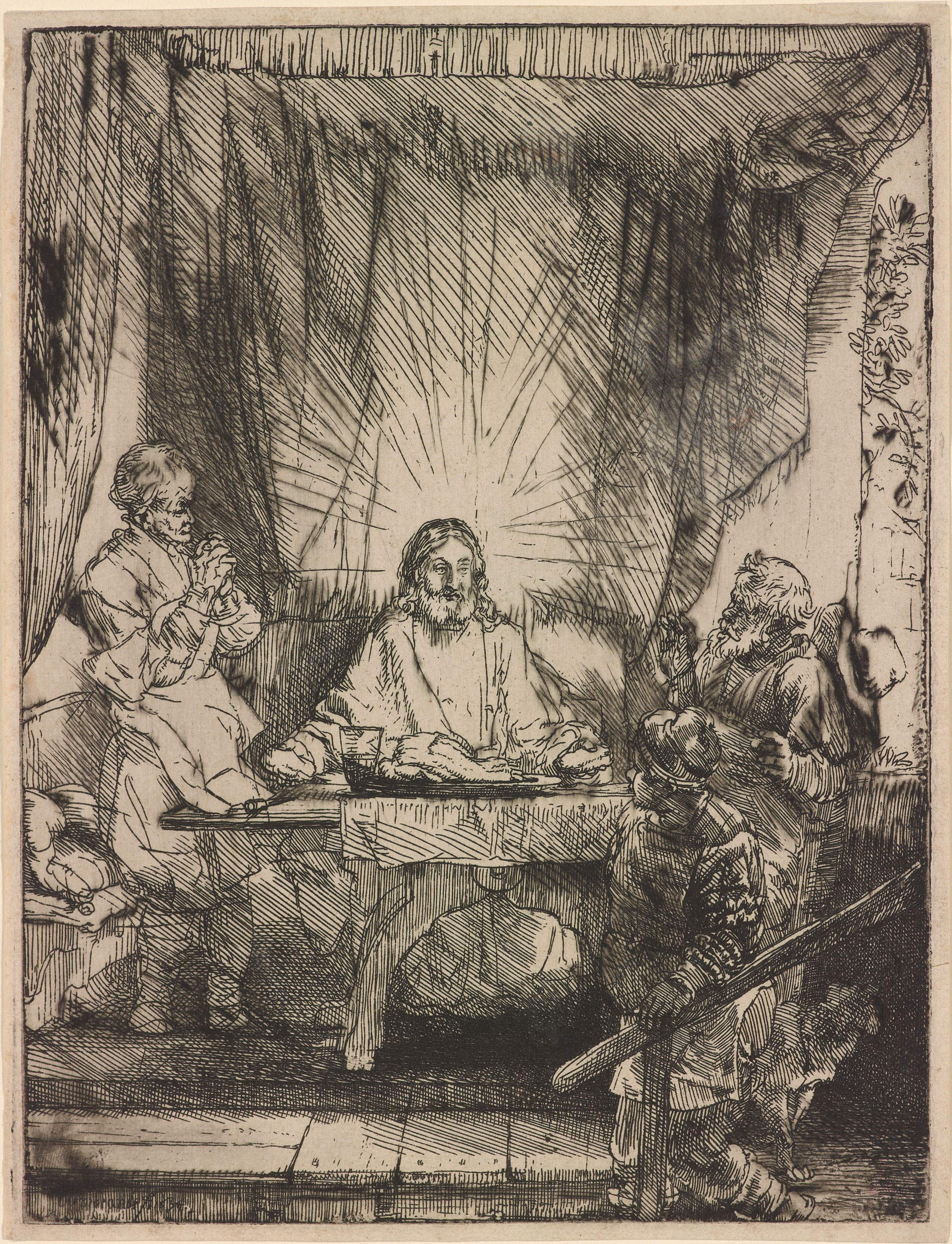

We have intentionally italicized the principal passages referring to the effects of great light and darkness, which are determined by the crescendo or pianissimo of the orchestra, so as the better to mark the similarity between the work of Rembrandt and that of Wagner. The stratagems of harmony, composition, vocal and orchestral instrumentation, concentrate the whole light upon one principal point, the scene of the Grail! The beautiful sonorous effects, mysterious and veiled, such as the master of Bayreuth conceived them, and executed them, coming from under the stage where all the orchestra is placed, are truly capable of making the illusion more complete, and causing a more intense emotion. These sounds, these effects of light and shade, are doubtless analogies between the mysterious and vibrating ray that is produced by the ecstatic and bloodless face of the Christ of Rembrandt in the Pilgrims of Emmaus, which we admire in the Louvre Museum!

Rembrandt, Pilgrims of Emmaus, or The Supper at Emmaus, oil on mahogany, 1648, Louvre, Paris

Has not the enigmatic physiognomy of Kundry a familiar look of the Magdalen of Christ and the Magdalen in the Brunswick Museum, where in this marvelous scenery of Good Friday the sinner kneels, humble and contrite, to wash the feet of Parsifal and, like a new Magdalen, stoops to wipe them with her long tresses?

Rembrandt, Christ and St. Mary Magdalene at the Tomb, oil on panel, 1638, Royal Collection, Windsor Castle, London

We venture to quote some extracts from the interesting work of Mr. Emile de Saint-Auban (note: A Pilgrimage to Bayreuth, 1892, pp. 202, 333, 334) who was also struck by the great affinities that exist between the geniuses of Rembrandt and Wagner. In the Good Friday scene, when Parsifal appears clad in armor by the side of Gurnemanz and Kundry, Mr. de Saint-Auban draws the following parallel:

'It is not the magic roar that we hear this time; the melodious forerunner does not come from the infernal regions; it is the harmonious image of the providential hero Parsifal who must be near… But is it not a ghost? The chords that precede his arrival have a sound from beyond the grave; they are phantom chords. So can I fancy the Leitmotiv of that Christ of Rembrandt, who, after His resurrection, appeared to the people of Emmaus in His deathlike splendor as a transfigured corpse!'

Rembrandt, The Risen Christ, oil on canvas, 1658, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Parsifal: The Savior’s Lament Leitmotiv

And, in his conclusion, Mr. de Saint-Auban lays special stress upon the similarity that can be noticed between the genius of Rembrandt and that of Wagner:

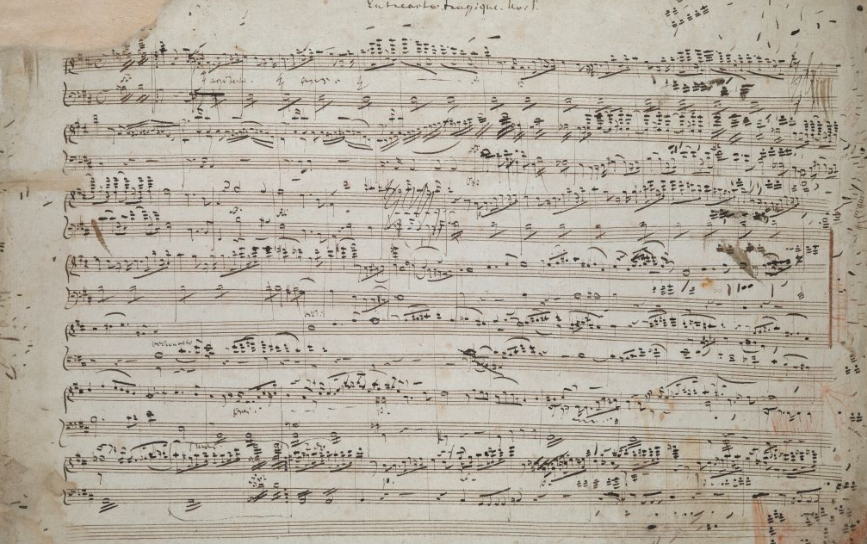

'The meditative study of a Wagnerian score evokes the recollection of a Rembrandt canvas. We stand before it; it is in powerful darkness; an incipient design is perceptible; then, again, comes darkness. The puzzled eye awaits a further development. Soon the clouds become animated, and spread their latent light. A richer light is kindled, dilates, expands, envelops its surroundings, penetrates them, searches them in their innermost crevices, glides upon the cornices, accentuates the angles, reveals all that is visible, and makes one anticipate the rest. From the black darkness men, groups, houses, furniture, glasses, potteries, familiar realities sally forth, each one playing a part; and far back in a corner you perceive a winding staircase leading up to a garret, down to a cellar, receding walls, rooms that grow bigger, and new expanses full of breath and life.'

Rembrandt, Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves (“The Three Crosses”), drypoint, 1653, Museum of Fine arts, Boston

Wagner, page from his manuscript score to Parsifal, his crowning work which took him 25 years to create (conceived 1857, completed 1882)

AWE Tip: Wagner's Early Original Manuscripts Online

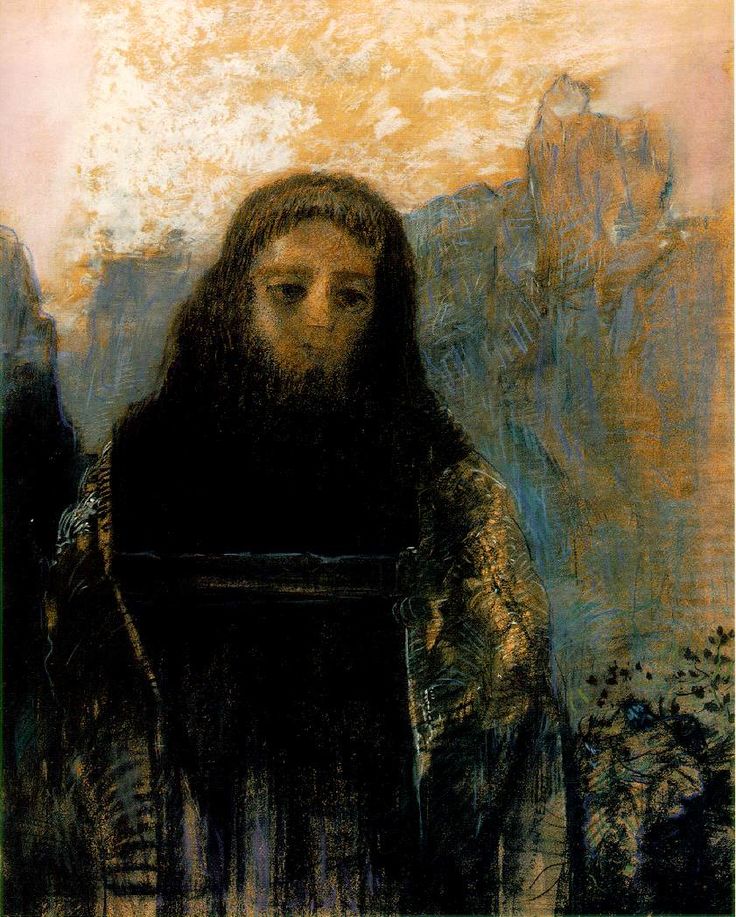

Rembrandt was not directly inspired by the sacred books, but by the legendary interpretation of them, which from century to century had become acclimatized among the people.

Before composing Parsifal, Wagner had, of course, thought of a life of Christ; but the legend obtained the upper hand, and it was the legend that guided his steps.

Both painter and composer rejuvenate tradition, and infuse into it a new life.

The consecrated themes are rendered without any rule or local veracity, but their spirit is so personal, so weird, that the subjects become impregnated with it, while it imparts to them an exalted and admirable expression.

The most exalted among these works of art almost always symbolize the feeling of sorrow in the Passion drama.

Rembrandt and Wagner have expressed with sublime intensity that poetic contemplation, that intimate comprehension of the sensation of pain, to which our nature has doomed us the moment we stand upon the threshold of life:

'Forse in qual forma, in quale

Stato che sia dentro covile o cuna,

E funesto a chi nascea il di natale!'

Whether we were born in high or low degree,

In a cavern or a mansion,

The day of our birth must bring sorrow to us all.

Leopardi (Canto notturno)

Wagner's Parsifal and the Good Samaritan of Rembrandt are dramas of Pity and of Faith.

Rembrandt, The Good Samaritan, oil on panel, 1630, Wallace Collection, London

...

The sword, buried to the hilt in the oak-tree of Hunding's hut, and suddenly shining with a brilliant flash, the quick irruption of light which flows into the dwelling the moment the door is thrown open by the strength of a vernal breeze, with the luminous effects of the orchestra underlying the whole, are these not pictures worthy of Rembrandt's brush?

Sieglinde tells Siegfried the story of Wotan’s appearance and how he struck the sacred sword Nothung in the ash tree stem; the great door in the hall springs open. Without is a lovely spring night; the full moon shines in and throws its bright light on the pair, who can now suddenly and plainly behold each other.

Orchestral score of Die Walküre

The orchestration of the principal passages presents the most striking analogies between the methods of Wagner and of Rembrandt; both possess the same art of bringing into full light the theme or principal motive, the one which produces the culminating point of sensation, of the idea which the author has propounded, and which he wishes the audience to conceive.

Study the orchestration of the 'Norns' scene in Götterdämmerung, the evocations of Alberich in the same work!

Orchestral score of Götterdämmerung

Consider the part played by the strings and the bass clarinet in the colouring of these pictures! Recall the storms in Die Walküre, the scene of the Nibelheim in Das Rheingold and in Siegfried the scene of Wotan and that between Alberich and Mime before the Dragon's cave (see below) – are they not so many dark pages, intensely black and mysterious, in strong contrast with the preceding or the following scenes, that are illumined by the brilliant orchestral colour and the feverish inspiration of the melody?

Siegfried, Act II, Scene 3 (2:45):

Scene between Alberich and Mime before the Dragon’s cave where they fight about the Ring

"Wohin schleich’st du, eilig und schlau, schlimmer Gesell?"

("Where are you slinking to, so slyly in such haste, you rascally rogue?")

Mime slinks on, looking about timidly, to assure himself of Fafner’s death. At the same time Alberich comes out from his cleft at the opposite side; he watches Mime narrowly. As the latter, not finding Siegfried, carefully steals towards the cave, Alberich darts upon him and bars his way.

The Nibelheim scene from the Ring Cycle production at the Metropolitan Opera, 2012. The breathtaking stage design created by Robert Lepage visually emphasizes the chiaroscuro effect inherent to Wagner’s music.

AWE Tip: Watch the trailer of the Ring Cycle at the Met and explore this staging at http://ringcycle.metoperafamily.org/.

Let us admire the second act of Tristan und Isolde, which is like a starlit, mysterious night, coming between the dazzling light of the first act and the sorrowful splendor of the third. Are not these contrasts of the Rembrandt school?

Tristan und Isolde, Acts II and III. Conductor: Daniel Barenboim. Stage director: Heiner Müller. Tristan: Siegfried Jerusalem, Isolde: Waltraud Meier. Bayreuth Festival 1995.

Details of the production

In the end of Act I of Tristan und Isolde, the crowning event, the arrival of the ship so long hoped for, is introduced by the unmixed brilliancy of beautiful sounds.

What a stage effect is produced, in a purely musical sense we mean, by the sudden irruption of this flash of light in the midst of the dark shades, where inexpressible sufferings were relentlessly, pitilessly meted out!

What object had Wagner at heart? It was to develop on the stage the inner motives of the action, to inculcate into the drama its utmost value; the musical elements, like all the other elements which he borrowed from the different branches of art, are only used to accentuate the action better. He imparts life to his heroes, and the Leitmotifs in the orchestra are most powerful agents in the enlightenment of their souls. He envelops them in a light of great intensity, and increased strength is borrowed from the darkness of the whole theatre at Bayreuth. Are not these the ideas, so dear to Rembrandt, which lend such animation to the different characters of the drama, that one gets an insight into their inner lives?

Interior of the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth, founded by Wagner in 1872 especially for the performance of his music dramas (first performance: The Ring Tetralogy, 1876). Photo courtesy of Agence Cb voyages

The great intensity of the drama is present in the works of both masters. Whether Rembrandt takes his subjects from legends, from the Scriptures, or from everyday life, he always invests them with supreme power by the aid of light and shade.

Whether Wagner is representing the heroes of the Edda, a spotless character like Parsifal, or the deeds of the Master Singers, he will always impart to them almost supernatural force by means of the forte, light, and the pianissimo, shade.

These two great geniuses always put their will into effect; all of their sublime conceptions were completely and perfectly carried out.

...

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait in Velvet Cap with Plume, etching, 1638, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Photo of Richard Wagner, 1868, by Henry Guttmann, Getty Images

Rembrandt and Wagner belong to that species of impulsive minds who entirely create their own aestheticism, borrow little or nothing from their predecessors, develop mysteriously, and leave no heirs. Rembrandt's pallet was so powerful, so foreign to all rules, that his most famous pupils sank their own individuality in his method. Will not the same happen to Richard Wagner's pupils? He had no pupils properly so called; but those of the young school who were hypnotized by his genius and his methods had much difficulty in becoming known. They copied the system, but really had no creative genius. Mr. Emile Michel, in his study on Rembrandt, shows clearly the danger of working under such masters:

'Logic alone cannot explain genius, especially Rembrandt's genius, which was perhaps the most original ever known. We lose ourselves in trying to follow him, and it would be rash to take him as a model. We do not think that his pupils had in him a very safe guide, or that his influence had a healthy effect upon their education. His powerful temperament compelled him to tower over them, and notwithstanding all the precautions he took to isolate them and safeguard their independence, they nearly all lost their own individuality through the mere strength of his ascendency. They were protected against the influence that they might exercise on one another, but they were defenseless against their master. The best among them, in their best works, succeed in being like him, and the highest honor that they have attained is that they are sometimes mistaken for him. But, as a rule, they only imitate his external methods, his quaintness, his modes of composition. They borrow his subjects, his costumes, his system of effects; they copy him, they counterfeit him; but his original and individual pride only accentuates the docility of their submissiveness.'

Are not these words applicable to Wagner and to his disciples? Fanaticized, they imitated him more than any other master had ever been imitated, and many amongst them who were mere copyists took exactly what should have been avoided.

...

Now, having endeavored to show the bonds that exist between the great Dutch painter and the great German symphonist and dramatist, we must state the points that separate them and distinguish the one from the other. A complete identification of them would mean the complete suppression of their originality. We may understand them better if we throw the light of the one upon the other, but it would be equally unjust to painter and musician if we were to confuse their two geniuses.

Eugène Fromentin, the remarkable painter and admirable writer, has defined, in his book, Les Maîtres D’Autrefois, chiaroscuro, or light and shade, of Rembrandt, as only a professional and an artist could define it. We cannot do better than quote him:

'The chiaroscuro is undoubtedly the incipient and necessary form of his impressions and of his ideas. Others besides him have used it; but none used it so continuously or so ingeniously. It is pre-eminently the mysterious form, the most hidden, the most elliptical, the richest in hints and in surprises that can be found in the picturesque language of the poets. It is light, vaporous, veiled, discreet; it lends its charms to hidden things, it excites curiosity, invests moral beauty with greater attraction, and gives more grace to the speculations of conscience. It is composed of sentiment, emotion, uncertainty, the indefinite and the infinite, dreams and idealism. And that is why the chiaroscuro is, as it should be, the poetic and natural atmosphere in which Rembrandt's genius ever dwelt.'

Rembrandt, The Holy Family with Painted Frame and Curtain, oil on panel, 1646, Museum Schloss Wilhelmshöhe, Kassel

This definition clearly shows that Rembrandt is, above all, the past-master of light and shade. His genius resides entirely in his etchings. His art is satisfied with black and white, which he bathes in a yellow mist in his oil paintings. Wagner, the magician of sound, also makes use of these spectral oppositions of daylight and darkness; he, too, is a great illuminator of darkness, but he is also a painter of extraordinary power, who requires the free run of the whole gamut of colours, because he alternately inhabits all the regions of nature, and deals with the whole scale of human passions.

Der fliegende Holländer

The harmonic and orchestral colouring of Richard Wagner resembles most the light and shade of Rembrandt, in one of his early works, Der fliegende Holländer, which, by the way, is founded upon a Dutch legend. This drama, the framework of which is composed of Norway and the North Sea, contains nothing but lightning and darkness, white upon black. The heroic and tender figure of Senta stands out luminously on the dark surf of the ocean which carries the accursed sailor.

Der fliegende Holländer, Act II (7:33): Senta’s ballad sung by the Swedish soprano Nina Stemme at her debut in Wiener Staatsoper, 2003

Tannhäuser

Peter Paul Rubens, The Feast of Venus, oil on canvas, 1635-36, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In Tannhäuser the sensual and pagan tendencies of Wagner burst forth in all their strength. In order to find analogies for the ballet of Venusberg alone, in the masterpieces of painters, we should have to combine Rubens, the painter of shuddering nudes, with Titian, who bathes his Fauns, his Bacchants, and his courtesans in the sumptuous light of Venice and of the Italian Tyrol.

AWE Tip: Venus with musicians theme in painting

Still from the Venusberg scene, designed and choreographed by Sascha Waltz in a breathtaking chiaroscuro manner for the 2014 production of Tannhäuser at Staatsoper Berlin. Credit: Mezzo TV

Lohengrin

The brilliant sonorousness of Lohengrin recalls the style of Correggio; diaphanous bodies on warm backgrounds, dazzling whitenesses upon rich yellow canvases. Here the light itself acts as a shade and as a contrast or set-off to the light. Recall the prelude which unfolds itself like a cloth of gold upon an azure sky, and the introduction of the third act, in which the flourish of the trombones rebel against the sparkling trepidation of the trumpets!

Correggio, Noli Me Tangere, oil on panel transferred to canvas, c. 1525, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Siegfried

Siegfried brings us to the freshness of the sunlit forest. Here we have innocent joy, light and warbling.

(musical excerpt note: Siegfried travels through the forest to find and kill the dragon Fafner and hears birdsong, trying to understand bird language and imitate it, all in vain.)

On the awakening of Brünhilde, torrents of light fall upon the whole creation. It is not only the Valkyrie who has been changed into a woman—it is the whole orchestra that seems to exclaim through all its chords and all its mouths:

'Hail, sun! hail, oh earth! hail, resplendent light!'

Götterdämmerung

In the farewell scene between Siegfried and Brünhilde in the first act of Götterdämmerung, the musician's magic concentrates, as it were, the blinding strength of the rising sun upon the heroic couple as they leave the cavern. Here the effects produced are so intense that the art of painting can provide no analogies to it, as they can only be found in the greatest effects of nature itself. The instruments all sounding together are, at that moment, drowned by the noise of the brasses and the cymbals, just as the rising sun re-absorbs and embodies for a moment all the colours of the sky and the earth.

Tristan and Isolde

How can we describe the death and the transfiguration of Isolde, who appears enveloped in pink gauze and caressed by the vast embrace of a setting sun? It seems then as if the sorrows, the ecstasy, the terrors of the great tragedy of love were vaporized and had resolved themselves in that ethereal pink as in an ocean of supreme unconsciousness.

Jessye Norman sings Isolde’s Liebestod aria "Mild und leise wie er lächelt..." ("Mild and softly he is smiling…"), finale of the whole opera, filmed against a magnificently quivering chiaroscuro background

***

It would be easy to furnish many more examples; but we have said enough to show how much more varied and exclusive is the gamut of Wagner's colours. We do not say so in order to deprecate the rare and original genius of Rembrandt, but to make it more evident by means of the contrast. This difference of the methods employed corresponds to a different conception of life and the human ideal.

Rembrandt is a dreamer who kindles life in the shadow, who etherizes light and spiritualizes the body. By means of his light and shade, composed of black and white, he gives us the sensation of the supernatural and the world beyond. He transports us to a mysterious region, that of the soul separated from nature, plunged in its own element and face to face with itself. He holds up a mirror to that soul in which it can fathom unknown depths. In a word, Rembrandt is a transcendent Spiritualist, as far as a painter can be.

On the other hand, the pantheistic genius of Wagner takes delight in the whole universe. He resorts to the kingdoms of nature, and analyses all the layers of the human soul. He is as much at home on the mystic heights whence comes Lohengrin, and to which Parsifal repairs, as he is in the abysses of diabolical wickedness and animalism from which Alberich and Ortrud have sprung. But one feels with him that it is the same breath that goes through the whole of his creation, that hell, heaven, and earth are joined together by infinite and necessary gradations, and that this great whole is but one real living creature.

The most sublime harmonies in Parsifal are still drenched by the tears of Christ. Wagner humanizes divinity, his heaven is only the crowning of earth. These are the reasons why his orchestration corresponds so marvelously with the definition which Schopenhauer gave of music:

'It roars, it sings, it cries, like the Soul of the world.'

Rembrandt, Simeon’s Song of Praise, oil on oak panel, 1631, Mauritshuis Royal Picture Gallery, The Hague, Netherlands

Galleries:

WAGNER

REMBRANDT

Credits:

Audio fragments are taken from the full edition of Wagner’s principal operas performed by Sir Georg Solti & Wiener Philarmoniker, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 1960-1987, Decca, 2012, mp3 format. All the excerpts are presented here for educational purposes only.

Leitmotif illustrations come from this edition: The Authentic Librettos of the Wagner Operas, Crown Publishers, New York, 1938, which we recommend to those who wish to explore the libretti of Wagner’s operas in detail.