By Dr. David Harrison, Project AWE Scholar

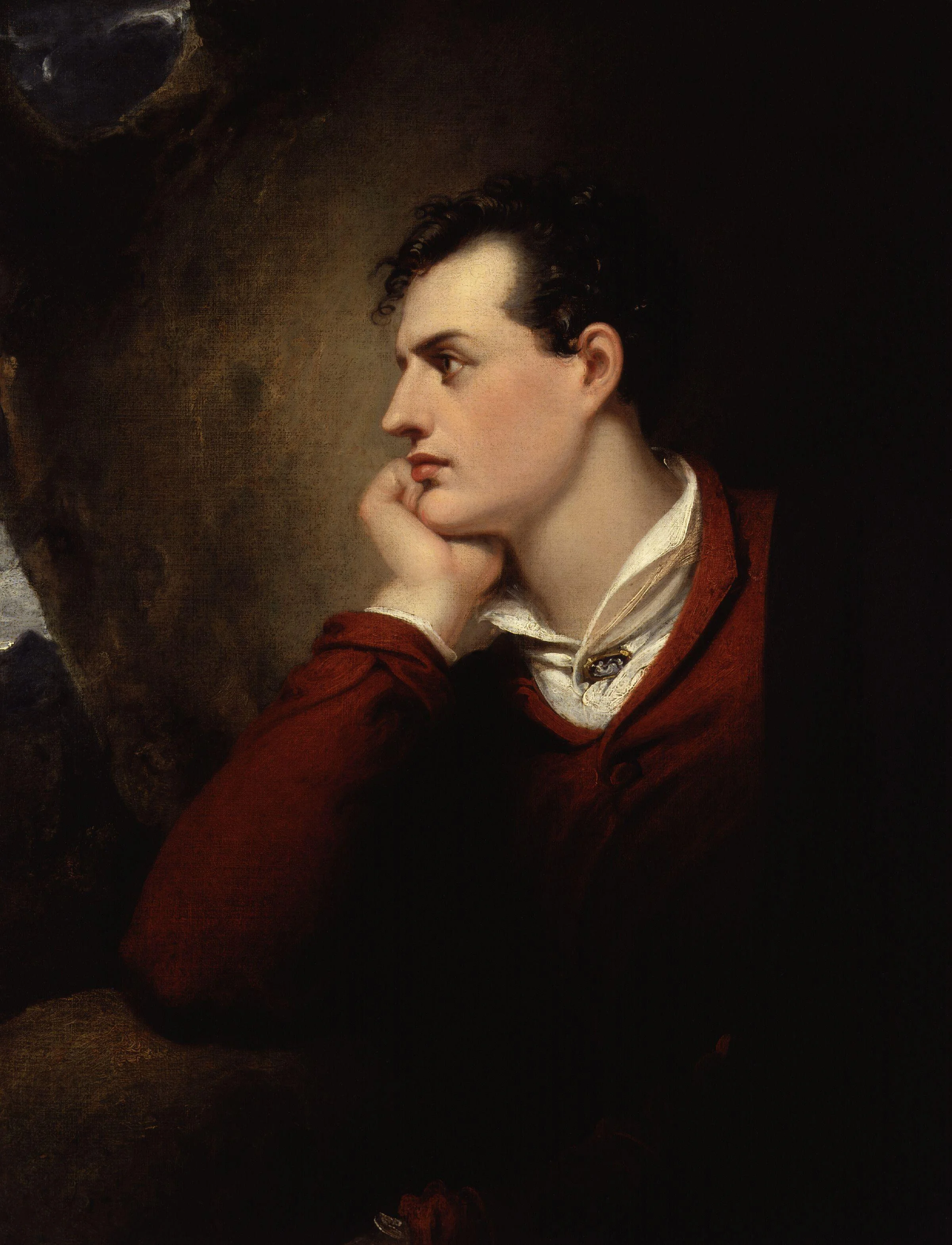

Fig. 1: George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron by Richard Westall

The eighteenth century was a period which witnessed the development of English Freemasonry as a social phenomenon, with the society undergoing constant transitions, modernizations and rebellions. The society had split into two main rival factions in 1751, with two grand lodges existing, the Moderns and the Antients, and as a result the society expanded, with Masonic lodges by both organizations being founded throughout England, Europe and the American colonies. The influence of the society on artists, writers and free thinkers was immense, and this paper will examine the influence of the Craft on one particular writer and revolutionary, the Romantic poet George Gordon Byron, the 6th Baron Byron.

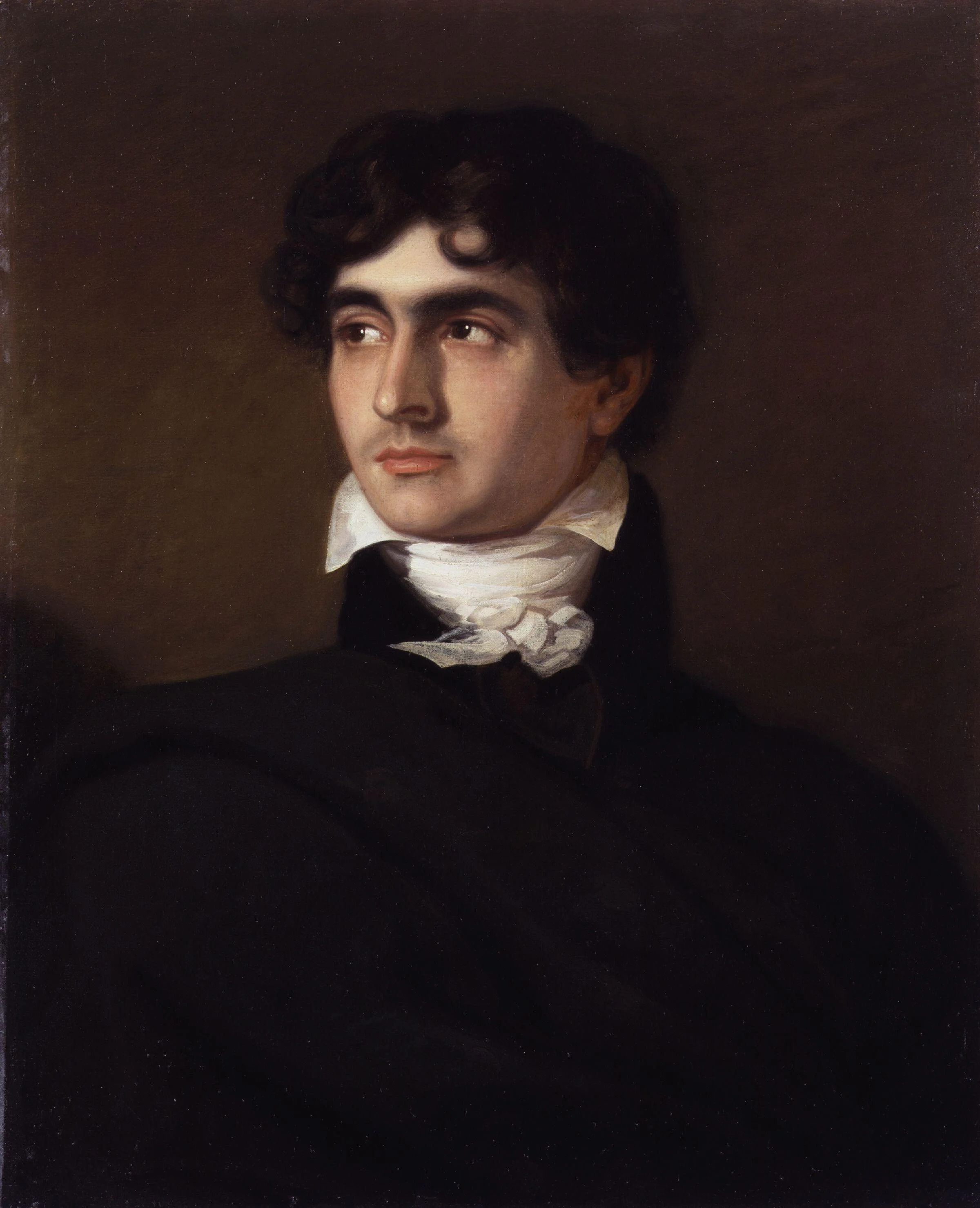

Fig. 2: Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage examines the theme of ancient architecture and the search for lost knowledge

George Gordon Byron (fig. 1) was born in 1788, and is regarded as a leading figure in the Romantic movement as well as one of Britain’s greatest poets. Byron also became known for his scandalous lifestyle, aristocratic excesses, and sexual and social intrigues, but even though he was not a Freemason, he did, as we shall see, have rather deep rooted connections to the society. After the publication of his first epic poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (fig. 2) in 1812, Byron was, for a time, the toast of Regency London; he was elected to the most exclusive of gentlemen’s clubs, he had affairs with desirable women, an affair with Lady Caroline Lamb led to her to label him with the immortal line ‘Mad, bad and dangerous to know’. Byron also took an interest in the same sex and was also rumored to have had an affair with his half sister. The scandals, rumors and gossip led to him leaving England for good in 1816.

Freemasonry certainly fascinated another writer who was linked to the Romantic movement; Thomas de Quincey, also known as the Opium Eater after his auto-biographical work that detailed his addiction to laudanum. De Quincey wrote the Origin of the Rosicrucians and the Free-Masons which was first published in January 1824, a work that attempted to examine the origins of these entwined secret societies. Though de Quincey was not a Mason, like Byron, he was aware of Freemasonry, the history and the nature of secret societies providing a profound interest. De Quincey, like the poets William Blake and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, also drew inspiration from the works of Emmanuel Swedenborg, the Swedish visionary who later lent his name to the Masonic Swedenborgian Rite.[1] Freemasonry certainly attracted poets such as Robert Burns, a Scottish Mason who is often observed as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement.

Fig. 3: Dr. John William Polidori (1795-1821) by F.G. Gainsford

The Poet and artist William Blake was also influenced by Freemasonry in his artwork, incorporating what can be interpreted as Masonic themes in works such as Newton and The Ancient of Days.[2] Another writer and friend of Byron’s who was a Freemason was Dr John William Polidori (fig. 3). Polidori was Byron’s personal physician who wrote the short Gothic story The Vampyre, which was the first ever published Vampire story in English. The story was based on Byron’s Fragment of a Novel – a story composed at the Villa Diodati by Lake Geneva in Switzerland in June 1816, during the same time Mary Shelley produced what would later develop into Frankenstein. Polidori became a Freemason in 1818,[3] his story being published the following year.[4]

The ‘Wicked Lord’

Byron’s great uncle, the eccentric fifth Lord Byron, had been Grand Master of the ‘Premier’ or ‘Modern’ Grand Lodge from 1747-51, and it may have been through him that the poet developed a familiarity with the themes of Freemasonry. As we shall see, Byron mentioned Freemasonry in his poetry, and commonly celebrated classical architecture in his work, discussing the many Temples of antiquity. Byron, who had been on the Grand Tour, continuously praised the lost knowledge of the ancient world, and in his epic poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, he attacked Lord Elgin for his plunder of the Parthenon, and expressed the hidden mysteries held within the classical Temples:

‘Here let me sit upon this massy stone,

The marble column’s yet unshaken base!

Here, son of Saturn! Was thy favourite throne:

Mightiest of many such! Hence let me trace

The latent grandeur of thy dwelling-place.

It may not be: nor even can Fancy’s eye

Restore what Time hath labour’d to deface.

Yet these proud pillars claim no passing sigh;

Unmoved the Moslem sits, the light Greek carols by.’[5]

Byron’s great uncle, the ‘Wicked Lord’, hosted regular ritualistic weekend parties on his estate Newstead Abbey, in a somewhat similar fashion to Sir Francis Dashwood’s Hell Fire and Dilettanti meetings at West Wycombe. The ‘Wicked Lord’ was a rather clubbable gentleman, being involved in an aristocratic dining club which met in the Star and Garter Tavern in London. However, true to his wild nature, he killed his neighbor William Chaworth during an argument, who was also a fellow member of his club, resulting in a murder trial in the House of Lords in 1765. He was eventually found guilty of manslaughter and, after the payment of a fine, he was a free man, though as a result of the scandal became a recluse, living in debt with his mistress in the decaying Gothic splendor of Newstead Abbey[6]. He certainly had a profound influence on his heir, the inheritance of the Gothic Abbey supplying a haunting and melancholy inspiration to the poet.

According to H.J. Whymper writing in AQC, the ‘Wicked Lord’ had been a popular and a somewhat charismatic Grand Master, and his absence during six out of ten Grand Lodge meetings was attributed to being on business out of the country. During his term as Grand Master he showed none of the temper or eccentricity of his later years, and the minutes of the Grand Lodge during his office revealed a Grand Master who was far from ‘Wicked’[7]. Whymper was indeed sympathetic to Byron’s Grand Mastership, and dismissed Gould’s view of the ‘Wicked Lord’, Gould having written that ‘the affairs of the Society were much neglected, and to this period of misrule, aggravated by the summary erasure of numerous lodges, we must look, I think, for the cause of that organized rebellion against authority, resulting in the great Schism.’ Gould clearly placing the blame for the formation of the ‘Antients’ with Byron.[8] Whymper put forward that Byron’s image was certainly tainted after his conviction of manslaughter, leading to his ‘unpopularity’ being ‘improperly seized upon to account for the dissensions in the Craft…’[9]

Lord Byron, Don Juan, the Carbonari and Revolution

Byron was certainly aware of Freemasonry, though he mentioned it only twice in his epic poem Don Juan. He first commented on the aristocratic networking aspects of the Craft in Canto XIII, Verse XXIV:

‘And thus acquaintance grew at noble routs

And diplomatic dinners or at other –

For Juan stood well both with Ins and Outs,

As in Freemasonry a higher brother.

Upon his talent Henry had no doubts;

His manner showed him sprung from a higher mother,

And all men like to show their hospitality,

To him whose breeding matched with this quality.’[10]

Byron seemed to be referring to the hierarchical system of Freemasonry, which at Grand Lodge level, was dominated by the gentry and led by certain charismatic aristocrats, Don Juan being portrayed as moving in well-connected and well-bred circles. He then touched upon the Craft once more in Canto XIV, Verse XXII of the same poem, commenting on the more mysterious and secretive aspects of Freemasonry:

‘And therefore what I throw off is ideal -

Lowered, leavened like a history of Freemasons

Which bears the same relation to the real,

As Captain Parry’s voyage may do to “Jason’s.”

The Grand Arcanum’s not for men to see all;

My music has some mystic diapasons;

And there is much which could not be appreciated

In any manner by the uninitiated’[11]

The alliteration of the words ‘Lowered’ and ‘leavened’ gives an emphasis to the mention of ‘a history of Freemasons’, a Masonic metaphor suggesting a transformation of sorts. Byron also refers to the ‘uninitiated’, and how they cannot appreciate the mystical secrets of the ‘Grand Arcanum’ and thus will never find what was lost.

There is no evidence of Byron being a Freemason, but he was a member of the Italian Carbonari, a Masonic-like secret society which shared similar symbolism though had a radical political ethos. Carbonari means ‘makers of charcoal’, though like Freemasonry, the secret society was of a speculative nature, and symbolically represented political and social purification, the brethren spreading liberty, morality, and progress. Having left England in 1816, Byron entered into a self-imposed exile to escape the scandalous rumours and mounting debt. It was during his period in Italy that Byron wrote parts of Don Juan, the leading character also becoming entwined in secret societies and political and sexual intrigue.

The Carbonari shared similar secret symbolism with Freemasonry, and met in lodges which, like Freemasonry, conducted a ritual. The Carbonari however were linked to militant revolutionaries in Italy who desired a democratic constitution and freedom from Austrian domination, and were the driving force behind the Naples uprising in 1820. Byron, being attracted to the rich political intrigue and the Romantic idea of revolution, was elected ‘Capo’ of the ‘Americani’, a branch of the Carbonari in Ravenna, where Byron stayed between 1819 – 1821, buying arms for the cause and meeting with senior members of the conspiracy.[12] Indeed, he writes excitedly of his Carbonari associations on February 18th, 1821:

‘To-day I have had no communication with my Carbonari cronies: but, in the mean time, my lower apartments are full of their bayonets, fusils, cartridges, and what not. I suppose they consider me as a depot, to be sacrificed, in case of accidents. It is no great matter, supposing that Italy could be liberated, who or what is sacrificed, it is a grand object – the very poetry of politics. Only think – a free Italy!!!’[13]

Another poet linked to the Carbonari was Gabriel Rossetti, whose revolutionary affiliations in Italy forced him into exile in 1821, and much later the Italian general Giuseppe Garibaldi became involved in the society during the early 1830s.[14] After their initial defeats of 1821, the Carbonari played a successful role in the July 1830 Revolution in France, but a subsequent rising in Italy resulted in failure and a government crackdown on the society ensued. By 1848 they had ceased to exist.

Byron subsequently became attracted to the Greek struggle against the Ottomans, and left for Greece in 1823. Taking up a similar role to what he had fulfilled with the Carbonari, Byron generously financing the Greek cause, paying for the so-called ‘Byron Brigade’ and arming the revolution. Byron found himself having to somewhat navigate the differing factions within the Greek cause, yet he embraced the war of independence wholeheartedly and was prepared to give his fortune in aid of the cause. However, Byron was to die in Greece of fever in April 1824 at the young age of 36. He is considered a National hero to the Greeks.

Newstead Abbey

Fig. 4: Solomon’s Seal on the drainpipes of Newstead

If one knows where to look when visiting Newstead Abbey, the ancestral home of Byron, one can find Masonic symbolism, for example the guttering is decorated with the Seal of Solomon (fig. 4), although this dates from the occupation of Colonel Thomas Wildman, a Freemason and an old school friend of Byron’s from Harrow, who eventually purchased the estate from the cash-strapped poet in 1818. Wildman became Provincial Grand Master for Nottinghamshire, and was a close friend and equerry to the Duke of Sussex, who visited Newstead on several occasions.

Fig. 6: The Masonic window in the chapel of Newstead celebrating the construction of Solomon’s Templ

Wildman constructed the Sussex Tower at Newstead in honor of the Grand Master, and improved the Chapter House as a private family chapel. When Wildman died in 1859, the estate was purchased by William Frederick Webb, who had the chapel re-decorated, and in memory of Wildman, Webb had a stained glass window designed with the central Masonic theme of the construction of Solomon’s Temple (fig. 5), which may also echo the building work that Wildman undertook at Newstead. Wildman founded the Royal Sussex Lodge in Nottingham in 1829, and there is also a Byron Lodge in the area which celebrates the Masonic links to the poet, his family and Newstead. Masonic services are still held at the chapel by the lodge.

The Masonic symbolism displayed at Newstead, along with the Solomon's Temple scene on display in the stained glass window, would be instantly recognizable to the initiated, the power and status of both the ‘Wicked Lord’ Byron and Colonel Wildman within Masonic circles being vividly apparent. A parallel to the Masonic themed stained glass windows and Masonic symbolism in the chapel at Tabley House in Cheshire can be seen here, with Lord de Tabley being the Provincial Grand Master of Cheshire during the later nineteenth century. There is evidence that Masonic services were held in the chapel. Lord de Tabley had a number of lodges named after him in the Cheshire area, including the De Tabley Lodge No. 941.[15]

The majority of English lodges in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, both Antient and Modern, met in taverns and Inns, but for a lodge to be deeply connected to a prominent local aristocrat, it was symbolic of status for that lodge to meet at his residence, providing a much more elitist and private meeting place. The residences of these important Freemasons became a status symbol proudly boasting the owners Masonic beliefs through the display of symbolism and became an erstwhile home to local lodges, lodges which the owners controlled. When fellow Masons visited the Hall, they could recognise the symbolism instantly, and also recognise the Masonic status of the owner. Houses such as Newstead Abbey and Tabley House both celebrated architecture, with the Gothic of Newstead and the classical design of Tabley House, both houses also celebrating Freemasonry, with both aristocratic families becoming central to Freemasonry in their own particular area, serving as Provincial Grand Masters, and all founding their own prestigious lodges. Newstead undoubtedly had a deep historic link to Freemasonry, and the additional feature of being the residence of the Romantic poet Byron would have certainly added to the status of the building especially amongst the more literary Masonic circles, as his reputation as one of Britain’s leading poets grew in stature as the nineteenth century progressed.

Conclusion

The poet Byron was certainly aware of Freemasonry and was attracted to the intrigue that certain secret societies offered, becoming a member of the Carbonari in Italy. His links to Masonry are certainly celebrated today with the Byron Lodge No. 4014 which still holds Masonic services in the chapel at Newstead Abbey, a lodge that also celebrates the Grand Mastership of the ‘Wicked Lord’ and of Colonel Thomas Wildman’s Provincial work in Nottinghamshire. Byron’s Masonic references in his poetry are few, however the Romantic themes of his verse certainly resound common Masonic themes of the celebration of ancient architecture and the search of what was lost. Perhaps in the end, Byron found his ultimate Romantic zeal in the cause of revolution, the Carbonari providing a society, like Freemasonry, filled with secret symbolism, but unlike Freemasonry, it supplied the poet with the passion of political change and the essence of Romantic revolt and rebellion.

Endnotes

[1] Polidori was a member of the Norwich based Union Lodge No. 52, Initiated on the 31st March 1818, Passed on the 28th April 1818 and Raised on the 1st June 1818.

[2] See John William Polidori, The Vampyre, (London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1819). See also Peter L. Thorslev, The Byronic Hero: Types and Prototypes, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962).

[3] See David Harrison, ‘Thomas De Quincey: The Opium Eater and the Masonic Text’, AQC, Vol. 129, (2016), pp.276-281. See also H.J. Jackson, ‘‘Swedenborg’s Meaning is the truth’ Coleridge, Tulk, and Swedenborg’, In Search of the Absolute: Essays on Swedenborg and Literature (Swedenborg Society, 2004). For the influence of Swedenborg on Blake see Peter Ackroyd, Blake, (London: QPD, 1995), pp.101-104. Ackroyd discusses how Blake eventually turned against the ideas of Swedenborg.

[4] David Harrison, The Genesis of Freemasonry, (Hersham: Lewis Masonic, 2009), p.97. See also Ackroyd, Blake, p.185-187.

[5] George Gordon Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, (London: Charles Griffin & Co., 1866), p.54.

[6] The Trial of William Lord Byron For The Murder of William Chaworth Esq; Before The House of Peers in Westminster Hall, in Full Parliament. London, 1765. Newstead Abbey Archives, reference NA1051.

[7] See H.J. Whymper ‘Lord Byron G.M.’, AQC, Vol.VI, (1893), pp.17-20.

[8] Ibid., p.17.

[9] Ibid., p.20.

[10] Leslie A. Marchand, (ed.), Don Juan by Lord Byron, Canto XIII, Stanza XXIV, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958), p.361.

[11] Ibid, Canto XIV, Stanza XXII, p.385.

[12] See R. Landsdown, ‘Byron and the Carbonari’, History Today, (May, 1991).

[13] See Leslie A. Marchand, (ed.), Byron’s Letters and Journals, Vol. VIII, ‘Born for Opposition’, 1821, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).

[14] See John Belton, ‘Revolutionary and Socialist Fraternalism 1848-1870: London to the Italian Risorgimento’, AQC, Vol.123, (2010), pp.231-253, in which Belton outlines Garibaldi’s Masonic career as Grand Hierophant of the Sovereign Sanctuary of Memphis-Misraïm between the years 1881-1882.

[15] See Harrison, Genesis of Freemasonry, pp.143-7.

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter, Blake, (London: QPD, 1995).

Anon., The Trial of William Lord Byron For The Murder of William Chaworth Esq; Before The House of Peers in Westminster Hall, in Full Parliament. London, 1765. Newstead Abbey Archives, reference NA1051.

Belton, John, ‘Revolutionary and Socialist Fraternalism 1848-1870: London to the Italian Risorgimento’, AQC, Vol.123, (2010), pp.231-253.

Byron, George Gordon, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, (London: Charles Griffin & Co., 1866).

Harrison, David, The Genesis of Freemasonry, (Hersham: Lewis Masonic, 2009).

Harrison, David, The Transformation of Freemasonry, (Bury St. Edmunds: Arima Publishing, 2010).

Harrison, David, ‘Thomas De Quincey: The Opium Eater and the Masonic Text’, AQC, Vol. 129, (2016), pp.276-281.

Jackson, H.J., ‘‘Swedenborg’s Meaning is the truth’ Coleridge, Tulk, and Swedenborg’, In Search of the Absolute: Essays on Swedenborg and Literature (Swedenborg Society, 2004).

Landsdown, R., ‘Byron and the Carbonari’, History Today, (May, 1991).

Marchand, Leslie, A., (ed.), Don Juan by Lord Byron, Canto XIII, Stanza XXIV, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958).

Marchand, Leslie, A., (ed.), Byron’s Letters and Journals, Vol. VIII, ‘Born for Opposition’, 1821, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).

Polidori, John William, The Vampyre, (London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1819).

Thorslev, Peter, L., The Byronic Her: Types and Prototypes, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962).

Whymper, H.J., ‘Lord Byron G.M.’, AQC, Vol.VI, (1893), pp.17-20.

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter, Blake, (London: QPD, 1995).

Anon., The Trial of William Lord Byron For The Murder of William Chaworth Esq; Before The House of Peers in Westminster Hall, in Full Parliament. London, 1765. Newstead Abbey Archives, reference NA1051.

Belton, John, ‘Revolutionary and Socialist Fraternalism 1848-1870: London to the Italian Risorgimento’, AQC, Vol.123, (2010), pp.231-253.

Byron, George Gordon, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, (London: Charles Griffin & Co., 1866).

Harrison, David, The Genesis of Freemasonry, (Hersham: Lewis Masonic, 2009).

Harrison, David, The Transformation of Freemasonry, (Bury St. Edmunds: Arima Publishing, 2010).

Harrison, David, ‘Thomas De Quincey: The Opium Eater and the Masonic Text’, AQC, Vol. 129, (2016), pp.276-281.

Jackson, H.J., ‘‘Swedenborg’s Meaning is the truth’ Coleridge, Tulk, and Swedenborg’, In Search of the Absolute: Essays on Swedenborg and Literature (Swedenborg Society, 2004).

Landsdown, R., ‘Byron and the Carbonari’, History Today, (May, 1991).

Marchand, Leslie, A., (ed.), Don Juan by Lord Byron, Canto XIII, Stanza XXIV, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958).

Marchand, Leslie, A., (ed.), Byron’s Letters and Journals, Vol. VIII, ‘Born for Opposition’, 1821, (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1978).

Polidori, John William, The Vampyre, (London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones, 1819).

Thorslev, Peter, L., The Byronic Her: Types and Prototypes, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1962).

Whymper, H.J., ‘Lord Byron G.M.’, AQC, Vol.VI, (1893), pp.17-20.

About the Author

Dr. David Harrison is a UK based Masonic historian who has so far written nine books on the history of English Freemasonry and has contributed many papers and articles on the subject to various journals and magazines, such as the AQC, Philalethes Journal, the UK based Freemasonry Today, MQ Magazine, The Square, the US based Knight Templar Magazine and the Masonic Journal. Harrison has also appeared on TV and radio discussing his work. Having gained his PhD from the University of Liverpool in 2008, which focused on the development of English Freemasonry, the thesis was subsequently published in March 2009 entitled The Genesis of Freemasonry by Lewis Masonic. The work became a best seller and is now on its third edition. Harrison’s other works include The Transformation of Freemasonry published by Arima Publishing in 2010, the Liverpool Masonic Rebellion and the Wigan Grand Lodge also published by Arima in 2012, A Quick Guide to Freemasonry which was published by Lewis Masonic in 2013, an examination of the York Grand Lodge published in 2014, Freemasonry and Fraternal Societies published in 2015, The City of York: A Masonic Guide published in 2016, and a biography on 19th century Liverpool philanthropist Christopher Rawdon which was published in the same year.